by

Nisha Desai

Categories: BlogTags: ART, Artists, colors, games, hospitality design, hotel design, interiordesign, interiordesigners, interiors, nature, Nisha Designs, ukraine

Leave a comment

Author: Nisha Desai

Hi, welcome to Nisha Designs.

Nisha Designs is the design studio of artist and textile designer, Nisha. This is where you can explore my artwork – each painting representing a magickal journey imagined spiritually and reflected physically with every brush stroke – buy paintings, and request commissions.

Nisha Designs is also home to my textiles business. I have 18+ years of experience working in the textile industry for Abercrombie Mills (Cone Jacquard Mill), Opuzen, Steven Harsey Textiles, Koni Hospitality, Welspun, Venus Group.

We provide custom and commissioned art, custom textile designs for hospitality and home textiles, as well as Art Direction services.

Whether its working with luxurious natural fibers – such as wools, cottons and organic linens – to designing your next bedding collection; to capturing the essence of a moment in nature through intricate brushstrokes on a canvas; or gathering nature’s little treasures – like stones, shells, leaves and feathers – to support me creatively in producing mood boards for art direction – Nisha Designs honors Mother Earth in all that we do, and creates with the utmost care and respect for the planet and her resources.

Natural Fibers- Nisha Designs

We love working with natural fibers. It brings a sense to our being, being present to our own home and life. Explore natural fibers and fabrics for your home and commercial properties. Invest in the greater good of the planets sources and resources that we do take it for granted. Be in gratitude do what needs to be done and explore natural fibers, fabrics. Because we all know planet will always survive with us in it or not. So while you are here make choices that serve the greater good of the whole. Choose natural no matter what the conditions of the society have been put in place there is growing and growth and abundance involved when we live from serving the greater good of the balance between chaos and order and do what needs to be done there is light and hope again.

If you willing to invest in new fibers to create new line of fabrics do contact us at nisha@nishadesigns.com. Link here.

The Magick of Hazel Tree- Learning through Nature- Nishante Divinelove- Nisha Designs

Learning through Nature: The Hazel tree holds an esteemed position, it is associated with wisdom and poetic inspiration, often depicted as a magical tree that bore nuts of knowledge. Its always good to learn and be aware about beings in our environment that inspires us and as to why they inspire us to have them in our fabrics, on our wall as art, on our clothing, as our food and to every part of our lives. Who are they and what makes them unique and how they interact with us, what they provide for us.

The Hazel tree holds an esteemed position in British folklore and mythology, with references dating back to ancient times. In Celtic mythology. In British folklore, it was believed that Hazel trees had protective properties, guarding against evil spirits. The tree was even said to bring luck to those who planted it near their homes.

Explore the medicinal and magickal properties, mythology stories and more here

Around the World in 80 Eco Spas: Life & Soul Magazine’s: Amber Purehill Hotel & Resort, Jeju, South Korea- Nisha Designs

32. Amber Purehill Hotel & Resort, Jeju, South Korea

Jeju Island’s Amber Purehill Hotel & Resort is the kind of place you seek out when you want to be surrounded by remarkable terrain, and where the landscape itself is the main experience. Often called Korea’s “Island of the Gods,” Jeju Island’s shaped by ancient volcanic activity and softened by centuries of wind and water: dramatic cliffs, dense forests, tangerine orchards, and a coastline that moves from black‑sand stretches to quiet, golden coves. Its rare UNESCO triple designation reflects how unusual the island is, but you sense that simply by being there, in the lava tubes beneath you, the crater lakes high above, and the subtropical forests alive with movement. It’s a landscape that feels both ancient and immediate, inviting you to pay attention to every shift in light and terrain.

The resort, Amber Purehill, sits in the island’s quiet inland heart, nestled into the forested slopes of Hallasan, the volcanic peak that rises as a guardian does over Jeju. Getting there is part of the pleasure. From Jeju International Airport, the drive takes around forty minutes, carrying visitors past stone‑walled tangerine farms, cedar groves, and the kind of countryside that makes you instinctively ease off the accelerator. Renting a car gives the freedom to explore Jeju’s patchwork of landscapes, though taxis and private transfers glide you directly to the resort’s entrance with the same sense of ease. As the road begins to climb toward the forest, the air cools, the trees thicken, and the island’s volcanic backbone reveals itself.

By the time you reach the resort’s elevation, 520 metres above sea level, it’s as if you’ve stepped into a quieter, more contemplative version of Jeju. Amber Purehill blends into this landscape with a calm, grounded elegance. Warm wood, soft light, and architecture shaped to welcome natural brightness create a sense of openness from the moment you step inside.

The rooms feel like sanctuaries designed for deep rest – high ceilings, wide windows, and a palette inspired by Jeju’s earth and sky. The design is minimalist in a generous way, using natural materials and uncluttered spaces to let the landscape do the talking. The view becomes part of the interior, shifting with the seasons: cherry blossoms drifting past your window in spring, lush green canopies in summer, fiery foliage in autumn, and a serene frost in winter. It’s a design philosophy rooted in Korean aesthetics and Jeju’s volcanic identity.

The nature‑first approach at Amber Purehill is no coincidence. Amber Purehill was created under the leadership of CEO Lee Myung‑yang, who envisioned a luxurious retreat that would “contain the beauty of Jeju’s natural scenery and the beauty of Korea”. His goal was to build a place where guests could experience complete rest in nature, with service and room quality on par with five‑star hotels but in a setting that feels deeply connected to the land. The resort’s architecture reflects that vision: structures that follow the contours of the mountain slope, interiors that rely on natural light, and materials chosen to echo the island’s volcanic palette.

Jeju offers endless ways to explore, and Amber Purehill sits in a perfect position to experience the island’s contrasts. Hallasan National Park rises nearby with trails that lead through ancient forests, volcanic rock formations, and sweeping viewpoints. Jeju’s Oreum trails – hiking paths up the island’s 300+ small, dormant volcanic cones – offer gentler climbs with panoramic views of the island’s quilted fields.

The coast is an easy drive away, where you can wander along the Olle walking paths, watch haenyeo divers emerge from the sea with their catch, or explore beaches that feel different on every side of the island. Waterfalls, lava tubes, botanical gardens, and cliffside viewpoints all sit within reach, turning each day into a choose‑your‑own‑adventure through one of Asia’s most diverse natural environments.

Amber Purehill’s Eco Scout Program adds another layer, guiding guests into Jeju’s wilder corners to learn about the island’s ecology and volcanic heritage – a gentle, engaging way to deepen your connection to the place. The resort’s spa deepens that connection even further. Alongside its seasonal Garden Spa blends and the serene Pure Sky Pool, the wellness programme draws inspiration from Korean healing traditions. Treatments often incorporate warm herbal compresses, mineral‑rich ingredients, and techniques rooted in jjimjilbang culture, creating rituals that feel both grounding and deeply restorative. Meditation and yoga sessions help you settle into the island’s pace, and the seasonal treatments shift with Jeju’s natural cycles, creating a sense of harmony between what’s happening inside and outside. It’s the kind of spa where time loosens its grip, and you emerge feeling as though your internal rhythm has finally synced with the land’s.

Back at the resort, the food experience mirrors the same thoughtful philosophy. Meals highlight seasonal ingredients, local produce, and the clean, comforting flavours Jeju is known for – fresh vegetables, island seafood, and dishes that feel nourishing after a day spent outdoors. Days on Jeju tend to unfold gently when you stay at Amber Purehill. A morning hike through forest light, an afternoon exploring the coast or wandering through tangerine orchards, a quiet return to the spa as the sky softens, and a peaceful evening meal that feels like a reward for simply being present. The resort gives you space – beautifully designed, deeply connected to its surroundings -while Jeju island itself does the rest.

Images Credit: Amber Purehill Hotel & Resort, Jeju

Year of the Horse- Chinese New Year 2026

Pegasus symbolizes powerful concepts like freedom, inspiration, and spiritual transcendence, representing the soul’s journey and divine purpose, born to embody poetic creativity, heroism, and pure power. It signifies breaking earthly bonds, bringing divine messages (like thunderbolts for Zeus), and serving as a conduit for artistic vision, bridging the earthly and celestial realms.

Wishing you all Happy Chinese New Year!!!

Lumber Jack, 100% Wool- Nisha Designs

Happy Valentine- Nisha Designs

The Magick of the Balloons: They represent freedom, joy, and the release of intentions, often used to send prayers or let go of past hurts. Their upward movement symbolizes transcending, hope, and connecting with the divine.

Wish you all a Happy Valentine.

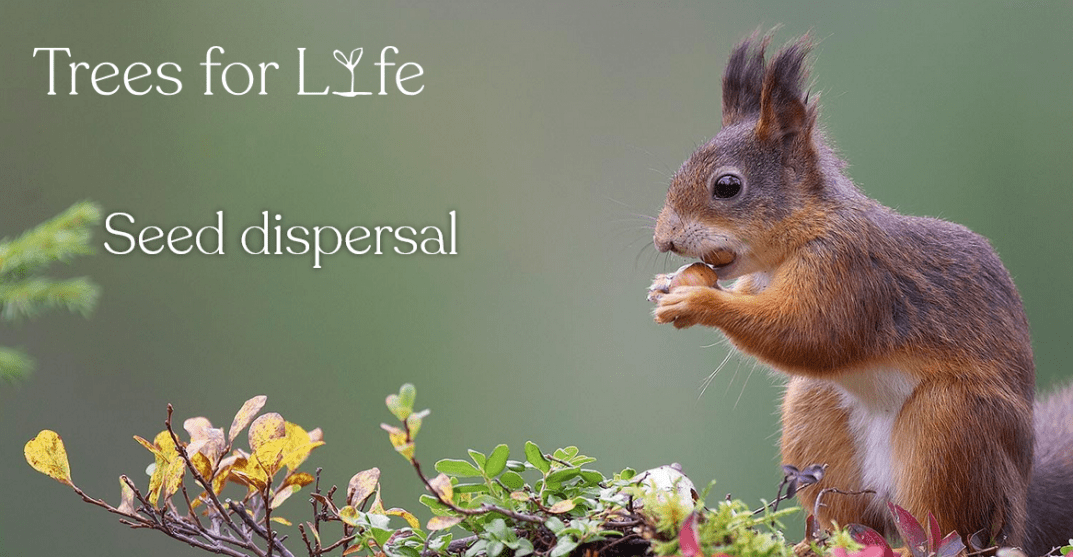

Seed Dispersal- Trees For Life- Rewilding the Scottish Highlands- Nisha Designs

Image Credit: Tree For Life. Source: https://treesforlife.org.uk/into-the-forest/habitats-and-ecology/ecology/seed-dispersal/

For anyone who walks through a forest, the most obvious living things all around will be plants. Less obvious, however, is how they ended up where they are. While animals can generally spread further afield quite easily, plants are less mobile. They have to use other means to help their seeds to disperse.

Ensuring that their own kind thrives into the future is high on the list of priorities for plants. It is also important that their offspring disperse. Being too crowded can result in too much competition for food, water and other essentials. It this happens, the species as a whole suffers. Colonising new sites also reduces the risk of a plant having all its proverbial eggs in one basket. If all members of a species are crowded into one area they are more at the mercy of chance. Fire or disease could easily seal the fate of a species in an isolated patch of forest. If they are more widely dispersed, this risk is reduced.

However, plants face a range of strategic problems. Imagine you are a plant setting seed: how will your seeds travel any distance and end up in suitable ground? How do you ensure your offspring have enough energy reserves to give them a good start in life? On top of all this there is the problem of making sure that at least some of your seeds manage to germinate, having run the gauntlet of seed predators. Plants (and fungi) have evolved some ingenious ways of getting around, as we will see with some of the many examples in the Caledonian Forest.

Blowing in the wind

There are many plant species in the Caledonian Forest that disperse through the air. This is an effective strategy, considering there’s no shortage of wind in the Highlands! Scots pine seeds are wind-dispersed, typically travelling up to 175 metres from their parent tree. In snowy landscapes, they can travel several kilometres, blown across the frozen surface. Birch also produces huge numbers of lightweight seeds. These come complete with two tiny wings that help them float on the air. Birch is a pioneer species, i.e. one that colonises a bare site rapidly and in large numbers. It was among the first tree species to arrive on the bleak tundra after the last Ice Age.

The seeds of plants such as rosebay willowherb and willows use downy hairs to help them get airborne. Even more sophisticated are the tiny parachutes on the seeds of members of the daisy family, such as thistles. This can ensure they travel much further, drifting on the breeze.

Orchids, such as creeping ladies-tresses invest in their seeds being almost powder-like – well suited to air travel. But because the seeds are so fine they do not have enough energy reserves to allow them to germinate. Like all orchids, they rely on mycorrhizal fungi to start them off. In this win-win relationship, the fungus provides the seedling with nutrients which it could not access on its own. In return the fungus can get sugars that the plant photosynthesises as it starts to grow.

Fungi and some plants such as ferns and mosses produce tiny spores that also carry easily on the breeze. Puffballs release their spores when rain, or an animal’s foot, puffs the spores through the hole in the top of the fruiting body. So puffballs have a number of dispersal allies, which can include animals, water and wind.

Water

While water is not used as commonly as wind to spread seeds, it plays an important role in dispersing those of alder. The wind can carry their seeds but their ‘wings’ also contain pockets of air. These help the seeds to float on the water and root further downstream. Alder is a water-loving tree so this a strategy helps it find good habitat. It is rare to see trees in rows in a natural forest, but with alder you can sometimes find lines of seedlings where they were deposited along the water’s edge. Seeds of some plants, such as marsh thistle and alder germinate on the water itself. By the time they are washed on to land, they are ready to root and grow.

‘Hitch-hiking’ on animals and birds

Dispersal by animals is fascinating, as the places the plants end up in is closely tied to the lifestyles and movements of the animals involved. Some plants have barbs on their seeds. Twinflower rarely sets seed, but when it does the seeds have small hooks that adhere to fur and feathers, allowing them to be carried to new sites. Humans also play a part in this process: we have carried seeds far beyond their normal range on clothes and shoes. Some seeds are dispersed and pushed into the ground by the hooves of large mammals. The loss of herbivores such as the aurochs has deprived the forest of an important seed disperser.

Birds are among the most mobile creatures, and there are many plants that have evolved to hitch a ride with them. As well as sticking to the outside, plants can tempt birds to swallow their seeds, and so carry them in their gut to other areas. Attracting the birds is crucial, and what better way to do it than with energy-rich berries? The bright red colour of berries such as rowan acts as an advertisement for birds, who have good colour vision. This is a true mutualistic relationship: both parties gain something from the bargain.

The second problem is how to protect the seed itself. After all, a bird’s digestive system is a forbidding place to be, with grinding gizzard (an extension of the gut packed with stones), and powerful acids. The stone that you spit out after eating a cherry is in fact hard casing, protecting the seed within. Wild cherry or gean and bird cherry have co-evolved so closely with birds that the seeds need this harsh treatment to break their dormancy.

It is quite common to see clusters of young rowan growing beneath a Scots pine, or even a single seedling within the pine’s branches. We can then deduce that a bird (typically a member of the thrush family) at some point sat in the branches of the tree, and passed the seeds out in its droppings.

Heavier seeds, such as nuts and acorns, have large energy reserves. This enables them to spend time getting firmly established, and giving them a better chance of surviving to maturity. However, all that weight causes problems with moving around, and oak seeds are very reluctant to germinate in the shadow of their parents.

Jays eat acorns and can carry them (up to six per flight) for several kilometres. These birds store the acorns by burying them, to eat at a later time. They often have a preference for burying them near a tree or shrub, at the edge of the forest. In four weeks they can bury as many as 7,500 acorns, and can remember the locations of them all! However, harsh weather and hungry predators will take their share of jays, allowing some seeds to germinate. Jays play an important part in dispersing oak woodlands.

Hazelnuts are often spread to new areas by red squirrels and mice, that may store them for later use. Again, while some seeds will be eaten, others aren’t reclaimed and manage to grow.

Remarkably, even ants can help to disperse the seeds of plants. Wood anemone and cow-wheat seeds have a small parcel of fatty tissue – called an elaiosome – attached to them. Ants take the seeds back to their nest so they can feed the elaiosome to their larvae, and so the seed is transported to a new location.

Other methods of dispersal

Some plants don’t invest much energy in complex mechanisms for dispersal. Bluebells or wild hyacinths are one example of a plant that simply drops its seeds directly to the ground. However, the result is that such plants will tend to spread and colonise new areas very slowly indeed.

There are plants that can disperse their seeds under their own power. Wood cranesbill has seed pods that explode when ripe, throwing the seeds away from the parent plant. Common dog violet uses this strategy, after which the seeds are sometimes spread further still by ants.

Some plants set seed very rarely, but can ensure their ongoing survival by generating clones of themselves. Aspen is one example. In Scotland, it rarely sets seed, but readily sends out suckers (known as ‘ramets’) from its roots. The young trees are genetically identical to the parent. The disadvantage here is that they miss out on the genetic variation and robustness that can result from sexual reproduction. The advantage is that they can survive in one area for thousands of years.

Dispersal in time

Other plants avoid competition by delaying their germination until a more suitable time. Heather produces many seeds which fall to the ground below. Some of these become dormant, forming a seed bank in the peat. If a fire sweeps through the area, the plants above ground may be killed, but the heat then warms the seeds to a temperature suitable for germination. They can then grow, free from competition.

Safety in numbers

As if transportation isn’t enough, plants have to ensure that at least some of their seeds avoid the many hungry mouths that inhabit the forest. One strategy to reduce the risk of seeds being eaten is utilised by hazel. The nut has a protective shell that requires effort to get into.

Many plants produce large numbers of seed to improve the chances at least some seeds surviving. Forest trees that have a lot of seed predators, such as Scots pine and oak, have ‘mast years’, in which they produce a huge glut of seeds every few years. Seed predators, such as jays or squirrels, have their fill, and while many seeds may end up in unsuitable ground, at least some are almost guaranteed to germinate. This does take a heavy toll on the tree’s resources however, and it may produce very little seed the following year to recover.

These cycles have a powerful knock-on effect in the forest ecosystem. The abundant food allows seed predators – herbivores such as rodents – to raise more young than usual, and there is a population explosion. This in turn can lead to an increase in weasels or other predators. However, in the barren period that follows, the expanded rodent population may crash once again.

Seed dispersal and ecological restoration

Understanding plant dispersal is important in restoring the Caledonian Forest, and other ecosystems. Ideally we use natural regeneration to restore a healthy forest. The problem is the further a site from the seed source, the less likely it is that seeds will colonise the area. Because trees such as Scots pine have seeds that travel relatively short distances, they are less likely to colonise more remote, denuded areas, even when they would be able to grow well there. Rowan berries, on the other hand, can be carried long distances. It is not uncommon to find rowan seedlings growing from the cracks in a rock in an otherwise treeless landscape. This knowledge helps us to prioritise what we plant – we rarely plant rowan, instead focussing on those trees that need most assistance.

The same principles apply to smaller plants. In the past Trees for Life’s Woodland Ground Flora Project aimed to identify those species of wildflower that are under-represented in more remote areas. For example, knowing that bluebells would be unable to cross highly fragmented areas by themselves makes them a priority for assistance. This is also the case with twinflower which, like aspen, rarely sets seed, instead spreading vegetatively.

Finally, understanding seed dispersal enables us to grow new trees in the nursery. For instance, the seeds of wild cherry have to pass through a bird’s digestive system for them to germinate. Knowing this, we have to use other methods to break the dormancy of the seeds, so that they will germinate in the nursery.

The plants in the Caledonian Forest are well equipped to disperse and regenerate, given the right conditions. But they are often hindered by forest fragmentation and overgrazing. In restoring forest ecosystems, humans are now consciously playing a positive role in dispersing wild plants.

Sources and further reading

- Begon M., Harper J.L., and Townsend C.R, (1996). Ecology (3rd ed.) Blackwell Science: Oxford.

- Detheridge, A. (2006). Ground flora regeneration in replanted Caledonian woodland in Glen Affric. Unpublished MSc Thesis. Imperial College, London.

- Fitter, A. (1987). New Generation Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain and Northern Europe. Collins: Glasgow.

- Grime, J.P. (1979). Plant Strategies and Vegetation Processes. John Wiley & Sons: Chichester.

- Suchockas, V.(2001). Distribution of Scot Pine (Pinus sylvestris) Naturally Regenerating Seedlings on Abandoned Agricultural Land at Forest Edges. Baltic Forestry, 7 (1): 79-83.

- Tree, I. (2018). Wilding – The return of nature to a British farm. Picador: London.

- Tudge, C. (2006). The Secret Life of Trees: How They Live and Why They Matter. Penguin: London.

- Wohlleben P. (2017). The Hidden Life of Trees. HarperCollins: London

Hempcell- Nisha Designs

Hempcell, blend of hemp and lyocell. Message us at nisha@nishadesigns.com for more information and visit here for more information on hemp, hemp blends, different weights, colors used for various applications and function in furniture, bedding, drapery, restaurants, cruise, hospitality, residential.

Being Present. Being in the Now- BBC Maestro- Nisha Designs

Being present sounds simple. And yet for most of us, it doesn’t come naturally.

Even when life slows down, our minds don’t always follow suit. We sit still, but our thoughts run ahead or loop backwards. We watch TV and scroll on our phones at the same time. We exercise while listening to our favourite podcast or song. Sound familiar?

In her course The Art of Being Present, Marina Abramović explores why presence is so difficult – and why learning to stay here, in the moment, requires far more than good intentions.

- Why are we not in the present?

- How to be more present

- How to live in the present moment

- Get a FREE lesson from artist Marina Abramović

Why are we not in the present?

According to Marina, the mind almost never stays where the body is.

We are trained to live in past and future – replaying what has already happened or rehearsing what’s yet to come. The present moment, she teaches, is the only place where reality actually exists, yet it’s the place we spend the least time.

Modern life reinforces this disconnection. We rarely do just one thing at a time. And when we do slow down, impatience quickly appears. The mind looks for distraction the moment an action feels boring or uncomfortable.

Rather than signs of failure, Marina Abramović treats boredom, irritation, and restlessness as evidence that presence is beginning.

Presence is hard because it asks us to stay – without distraction, without outcome, without escape.

How to be more present

Abramović does not teach presence as a concept. She teaches it as a practice, grounded in the body.

One of the first principles is surrendering control. Presence cannot be forced. The moment we judge whether an exercise is “working,” or expect a particular feeling, the mind takes over again. Her approach begins by letting go of expectation and committing fully to the action itself.

Breathing plays a central role. Thinking is almost constant, but when we slow down our breath, the thoughts in our mind begin to slow too. In the brief gap between these thoughts, you can start to feel presence appear.

She also emphasises doing one task at a time. And committing to just that. Some exercises in her course explore drinking water consciously, walking slowly with full attention, or writing your name without lifting the pencil for a long time.

These acts are intentionally simple, yet challenging, because they leave no room for mental escape.

How to live in the present moment

So how do you practice this in daily life?

In The Art of Being Present, Marina emphasizes that presence is not a mindset you adopt, but a state you enter through action. Her exercises are deliberately simple, designed to remove distraction rather than add stimulation.

Here are a few ways to practice presence – some drawn directly from her work, others more commonly recognized – that all share the same principle: doing one thing, fully.

1. Commit to duration

Many of Marina’s exercises work because they last long enough for resistance to surface – and then pass. Some start at 15 minutes and other around an hour long. Some practices are encouraged to try for a few days. The idea is that you push past those uncomfortable feelings.

“When you sit still for ten, fifteen, twenty minutes, your body itches, and you desperately want to move. But if you actively exert willpower, generate willpower, and refuse to move no matter what, then you will open the door to the human soul.”

2. Do one everyday action slowly

Drink a glass of water, walk, or sit in a chair without multitasking. Stay with the sensations of the action itself, rather than thinking about time or outcome.

3. Slow your breathing

When breathing becomes conscious and deliberate, thinking naturally begins to slow down. If you’ve ever meditated or tried practices like Yoga, that ask you to tune inwards, you may have already experienced this feeling.

4. Commit to duration

Many of Marina’s exercises only work because they last long enough for resistance to surface – and then pass. So, it’s important to carve out enough time in your day to day lives to try some of these exercises. Aim for 1 hour, and if not, try 30 minutes.

5. Ground yourself physically

If you can, find grass to stand on. Standing firmly on the earth, feeling weight through the feet, or connecting with natural elements brings attention out of the mind and back into the body. Some people practice this barefoot; others prefer to do so with shoes on.

6. Reduce sensory input

Silence notifications, remove background noise, or step outside. Fewer stimuli make it easier to stay with what’s happening now.

“Deprivation of technology is so important,” says Marina.”The first thing that you’ll do is take your phone, switch it off. No computer (and) no watch.”

7. Let go of productivity goals

If you focus too much on the feeling you’re aiming to get to, you might not achieve the result you’re hoping for.

Presence deepens when actions are done for their own sake, not to achieve a result. So go easy on yourself. You might need to practise exercises more than once to feel benefit.

The present moment isn’t something we reach once and keep forever. It’s something we return to again and again – through the body, through attention, through letting go of expectations.

Some of these practices echo ideas explored more fully in our guide to feeling calm, where slowing down and staying with sensation plays a key role in regulating the nervous system.

Marina’s work reminds us that presence is not passive. It requires endurance, commitment, and honesty. But within that commitment, time softens, thinking loosens, and something real finally comes into focus.

Want to explore this practice more deeply? Marina Abramović’s course The Art of Being Present guides you through the exercises behind these ideas, showing how presence can be trained, slowly and deliberately, through everyday actions.

Bast Hemp Collection- Nisha Designs

Bast Hemp Collection: Natural + Sustainable Hemp Fabric

The finest collection of natural fiber fabrics from China, Romania, the Eastern Bloc of Europe, parts of Mexico and South America. Our manufacturer and developer of over 1000 hemp fabrics world wide, and a leading consultant for the hemp fiber industry.

Email us for samples, more information at nisha@nishadesigns.com and visit our site for more details about our beautiful Hemp Fabrics.

100% Wool Collection- Sustainability- Nisha Designs

We have beautiful selective patterns of 100% Wool. Sustainable, Naturally Fire Retardant. Email us for more details at nisha@nishadesigns.com and visit our page for more information.